Every club player has experienced it: you step onto the court with a can of balls you opened two weeks ago, and after a few groundstrokes, something feels off. Your timing is fractionally late. Balls that should land deep are clipping the service line. Your opponent’s slice is sitting up instead of skidding low.

The balls look fine. The felt isn’t shredded. But they’re already compromised, and most recreational players don’t realize how quickly this happens, or what it costs them in terms of stroke development and physical stress.

Understanding why tennis balls lose their performance characteristics so rapidly, and learning practical strategies to manage this reality, can improve your practice quality and potentially reduce your risk of injury. Here’s what every serious recreational player should know.

Tennis balls lose internal pressure within days of opening due to air diffusion through the rubber shell. This is separate from felt wear and happens even if balls aren’t used. Dead balls compromise timing, depth control, and practice quality by providing inaccurate feedback that doesn’t transfer to match conditions. Smart rotation and proper storage (using pressurized containers between sessions, reserving fresh balls for matches and technical work) extends ball life without requiring fresh cans every time you play.

How Pressurized Tennis Balls Actually Work

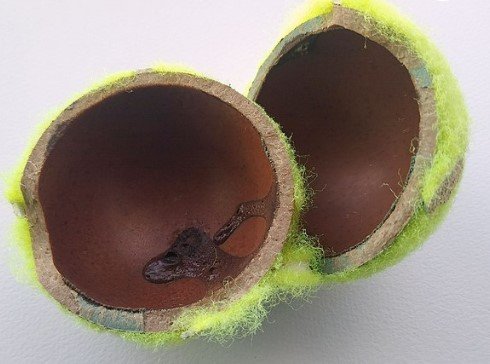

A regulation tennis ball is a precisely engineered product. According to International Tennis Federation specifications, the rubber core contains approximately 12 pounds per square inch (80 kPa) more pressure than sea level ambient air pressure, which is about 14.7 psi. This internal pressure is what gives the ball its bounce and responsiveness.

When you strike a pressurized ball, the compressed air inside acts as a spring, rapidly deforming and recovering to generate the ball’s characteristic lively bounce. The felt cover serves a different function: it creates aerodynamic drag, generates spin through friction with the strings, and protects the rubber core.

Here’s the problem: rubber is semi-permeable and not perfectly airtight due to its porous nature. The moment a can is opened, the pressurized air inside the ball begins diffusing through the rubber shell into the surrounding atmosphere. This process is continuous and irreversible under normal conditions. Within hours of opening, pressure loss begins, and within days it accelerates.

Pressure Loss vs. Felt Wear: Two Different Problems

Recreational players often confuse two distinct forms of ball degradation:

Pressure Loss

Pressure loss affects the ball’s internal dynamics. As air escapes, the ball becomes less responsive. It bounces lower, comes off the strings with less velocity, and feels “heavy” or “dead.” This happens whether you play with the balls or not. It’s purely a function of time and environmental conditions.

Felt Wear

Felt wear is mechanical degradation from use. The fuzzy nap flattens, fibers break down, and eventually the felt may separate from the rubber. This affects spin generation, aerodynamic stability, and ball control. A ball can maintain good pressure but have worn felt, or have pristine felt but be completely dead from pressure loss.

For recreational players, pressure loss typically becomes noticeable before significant felt wear occurs, especially if you’re playing once or twice a week with the same can of balls.

How Dead Balls Undermine Your Game

The consequences of using under-pressurized balls extend beyond simply feeling sluggish:

Timing and Depth Control Deteriorate

Your brain and muscles calibrate stroke timing based on ball speed and bounce height. When balls slow down from pressure loss, your timing cues become unreliable. Shots you’ve grooved for months suddenly land short because the ball isn’t carrying as deep. This forces compensations (often hitting harder or with altered swing paths) that can embed bad habits.

Practice Quality Suffers

If you’re drilling with dead balls, you’re not simulating match conditions. Your footwork patterns, court positioning, and tactical decision-making are all based on inaccurate ball behaviour. The gap between practice and competition widens.

Physical Stress Increases

Lower-bouncing balls force you to bend lower and swing more aggressively to achieve the same depth and pace. Over extended sessions, this places additional stress on the shoulder, elbow, and wrist. While a single session might not cause injury, the cumulative effect over months matters, particularly for players with pre-existing joint concerns.

Why Recreational Players Use Old Balls (And What It Costs)

Club players commonly use balls for weeks or even months after opening. The reasons are understandable: cost concerns, environmental consciousness, or simply not noticing the gradual degradation. A new can costs $3 to $6, and opening fresh balls every session feels wasteful.

This frugality has trade-offs. Using significantly degraded balls is the practice equivalent of a guitarist learning on a badly tuned instrument. You’re adapting to incorrect feedback. The better strategy is to differentiate between uses, not to replace balls constantly.

Practical Strategies for Managing Ball Life

You don’t need to open fresh balls every time you hit, but you should be strategic about rotation and storage. Research shows that at a recreational level, a can of pressurized tennis balls will last anywhere between 1 to 4 weeks of light to moderate play:

1. Implement a Rotation System

Reserve new or lightly used balls for matches and competitive practice. Use older balls for warm-ups, serving practice, or solo drills where ball response is less critical. Mark cans with dates to track age.

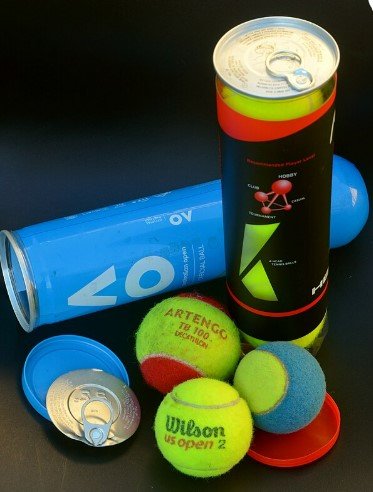

2. Store Balls in a Pressurized Container Between Sessions

A pressurized ball storage system maintains external pressure around the balls, reducing the pressure differential that drives air diffusion. This can extend usable life by weeks.

These systems range from simple pumped canisters to more sophisticated designs. One established option is Pressureball, which uses a manual pump with a special container and seal to maintain pressure almost indefinitely.

3. Avoid Temperature Extremes

Heat accelerates pressure loss by increasing molecular activity in the rubber. Don’t leave balls in your car trunk in summer. Conversely, very cold balls (below 40°F) bounce poorly regardless of pressure status, though cold doesn’t permanently damage them.

4. Consider Altitude

If you play at significantly different elevations (mountain resort vs. sea level), be aware that balls pressurized at sea level will feel livelier at altitude where atmospheric pressure is lower, creating a larger pressure differential.

5. Buy in Bulk During Sales

If cost is the primary concern, purchasing cases during seasonal promotions (often 20 to 30% off) makes fresh balls more economical. Unopened cans maintain factory pressure for about two years before gradual leakage through small holes in the packaging causes pressure loss.

6. Recognize the Signs

A ball should be retired from serious play when it bounces noticeably lower from chest height, produces a dull sound rather than a crisp pop off the strings, or feels sluggish through the air. According to ITF regulations, a regulation ball dropped from 100 inches must rebound between 53 and 58 inches, and as air leaks out, the bounce gets progressively lower. Trust your tactile sense.

7. Track Ball Age for Structured Practice

If you’re working with a coach or following a structured improvement plan, use fresh balls for technical work. Save older balls for fitness drills or casual rallying.

8. Match Your Balls to Court Surface

Hard courts are more demanding on felt than clay, accelerating felt wear. On hard courts, pressure loss typically becomes the limiting factor before felt is destroyed. On clay, felt wear may become noticeable first.

Common Myths About Reviving Dead Tennis Balls

Several folk remedies claim to restore pressure to dead balls. Let’s examine these myths:

Refrigerator or Freezer Storage

Cooling a ball temporarily increases internal pressure slightly due to thermal contraction, but this reverses as soon as the ball warms up. You haven’t added air; you’ve just changed its temperature. More importantly, moisture in refrigerators can degrade felt.

Sealed Plastic Bags or Jars

These prevent further pressure loss relative to open air, but only if sealed immediately when balls are new. A sealed bag around already-dead balls accomplishes nothing. The balls and surrounding air are already in equilibrium.

Re-pressurizing with a Bike Pump

You can’t inject air into a sealed tennis ball without destroying its structural integrity. Professional ball manufacturers use specialized equipment during production. DIY pressurization doesn’t work.

The only method that extends pressure life is storage in a container where external pressure is actively maintained above atmospheric pressure, reducing the pressure gradient that drives air diffusion through the rubber.

A Coach’s Perspective

Experienced teaching professionals consistently emphasize the connection between equipment quality and skill development. Players who train exclusively with degraded balls often develop stroke compensations that don’t translate to match play. The timing disruption is particularly problematic for intermediate players (USTA 3.5 to 4.0) who are refining shot consistency.

From a coaching standpoint, the investment in maintaining ball quality is small relative to lesson costs or court time. If you’re paying $60 to $80 per hour for instruction, using dead balls during that session undermines the entire investment. Fresh balls should be considered part of the cost of serious practice, not an optional luxury.

For players managing tennis elbow or shoulder issues, ball quality becomes even more relevant. Dead balls require more muscular effort to generate pace and depth, increasing repetitive stress. This doesn’t mean ball quality causes injury, but it can be a contributing factor worth addressing.

The Bottom Line

Tennis balls are consumable equipment, designed for a limited performance window. Recreational players often extend that window far beyond what’s optimal for skill development. While you don’t need fresh balls for every session, understanding the mechanics of pressure loss and implementing a smart rotation strategy will improve your practice quality and potentially reduce physical stress.

The key is differentiation: use appropriate balls for the task at hand. Match play and technical practice deserve fresh balls. Warm-ups and fitness work don’t. With thoughtful management, you can maintain quality without excessive cost.

Read more of our exclusive feature articles here.

Read more of our player focus articles here.

Follow The Tennis Site on Facebook and X: @thetennissite

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.